British Garden of Peace – “No Man’s Land”, 2025

The garden is inspired by Richebourg’s history during the First World War and aims to blend the landscapes of Sussex and northern France. It reflects the healing power of nature in response to the physical and emotional wounds of war.

The Battle of the Boar’s Head, near Richebourg, took place in June 1916. In less than five hours, the three South Downs battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment lost 366 men, including 12 sets of brothers and three brothers from a single family. A thousand others were wounded or taken prisoner. This battle became known as “The Day Sussex Died.” The tragedy inspired the design of the Garden of Peace.

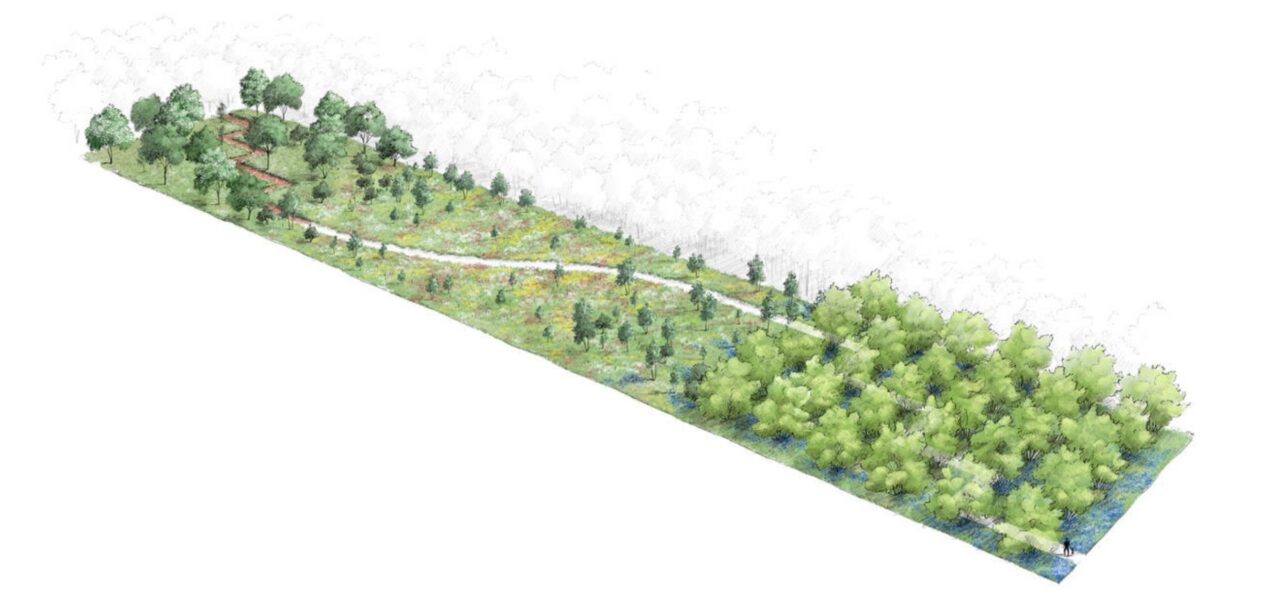

Visitors enter the garden through a coppiced hazel woodland, typical of Sussex, with a carpet of bluebells and woodland flowers. The trees gradually thin out to reveal a few birches and oaks—pioneer species—stretching out into the “No Man’s Land” meadow. This wildflower meadow is crossed by a white path, echoing the chalk cliffs of Sussex. A wooden bench offers a place for rest and reflection. The path, initially white chalk, later becomes brick and leads into an old orchard, where fruit trees stand amid wildflowers growing at their base.

A wartime map of Richebourg, showing the Battle of the Boar’s Head, includes supply trenches named after fruit trees and orchards: Orchard CT, Plum Street, and Pear Street. The nearby Saint-Vaast Military Cemetery was once an orchard where soldiers were buried.

Access to the garden is from Rue de la Briqueterie, the site of a former brickworks. After the First World War, many factories were built in northern France to produce bricks for reconstruction. Brick, a traditional building material in Flanders, is used here to evoke that period of renewal. The dark mortar joints reference the black spoil heaps of the nearby mining industry.

The garden represents the trenches and no man’s land typical of the 1914–1918 war. The zigzag layout of the paths is inspired by the crenellated pattern of combat trenches visible on military maps of Richebourg.

The South Downs are a vast chain of chalk hills stretching between Hampshire and Sussex. The word “downs” comes from the Old English dun, meaning hill. This landscape has been shaped by human activity since the Neolithic period. On these hills, a thin layer of soil over chalk supports rare grasslands rich in wildflowers. Grazing sheep leave white paths, as depicted in Eric Ravilious’s 1935 painting Chalk Paths.

In the valleys of the Sussex Weald, woodlands were coppiced to produce timber for fencing and charcoal-making. Coppicing involves cutting trees every 7 to 10 years, encouraging rapid regrowth without killing the tree. This sustainable cycle ensures a continuous supply of wood. The English word coppice derives from the French verb couper (to cut). When a woodland is coppiced, a clearing is created, exposing seeds in the soil to sunlight and encouraging germination. Coppiced woods host a rich flora, with emblematic plants such as bluebells, wood anemones, and wild garlic.